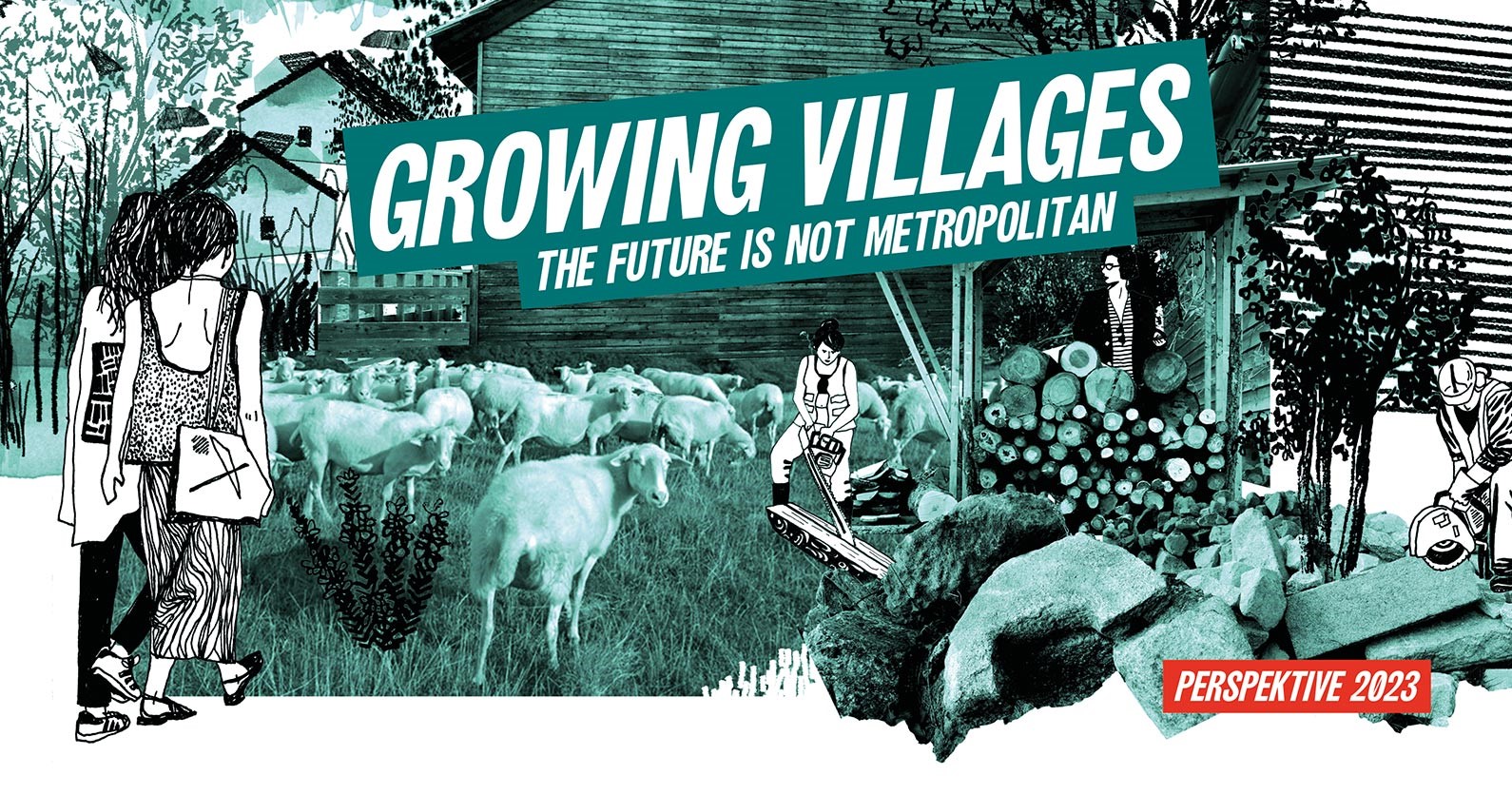

PREISTRÄGER/INNEN 2023

Der Fonds PERSPEKTIVE 2023 und sein Initiator, das Bureau des arts plastiques des Institut français Deutschland, freuen sich, die Gewinnerprojekte des Ideenwettbewerbs GROWING VILLAGES – The future is not metropolitan bekannt zu geben.

.

Die Bewerber*innen wurden aufgerufen, sich das Dorf von heute oder sogar der Zukunft vorzustellen. Ein Dorf, das sich weiterentwickelt, wächst und gedeiht, ohne dabei zu einer Großstadt zu werden. Ein soziales und gesellschaftliches Gebiet, das die Natur respektiert …(die Ausschreibung einsehen)

.

- Der erste Preis geht an das Projekt The caretakers – An exploration on a traumatized landscape von Cécile Gaudard (geb. 1998 in Orcines, Frankreich

. - Der zweiten Preis geht an das Projekt Transhumance: a model for growing villages von Kim Tzarowsky (Berlin) und Maria José Landeta Valencia

. - Den dritten Preis geht an das Projekt Kooperatives Hinterland von Sarah Pens (geb. 1997 in Hannover)

.

- Das Unbequeme Dorf von Benedikt Hartl

- Make Ines stay? von Johanna Bendlin, Laura Villeret und Falma Fshazi

- Always there, very personal von Sunghoon GO

- Achkarren-Growing and Sustainable village, von Pavel KOSENKOV

- Rethinking villages – Reinventing Reurbanism von Franziska MICHL

- Cross-Border Placemaking, von Alexandra SCHARTNER

- Rutopie – rural, village, future von Leonie WREDE

.

Ausschreibung Achitektur Ideenwettbewerb 2023 – Growing villages

Deadline 31.08.2023

PERSPEKTIVE ist ein deutsch-französischer Fonds für kreativen Austausch, der 2014 vom Büro für bildende Kunst des Institut français Deutschland ins Leben gerufen wurde.

Marie Graftieaux, Leiterin

Alix Weidner, Kulturbeauftragte

Bildnachweis: Ninon Bonzom, “La montagne limousine, une forêt habitée ?” collage, 2018, aus ihrer Abschlussarbeit an der Hochschule für Natur und Landschaft (INSA CVL) in Blois, Frankreich. Design: Charlie Jouvet

Sophie Delhay

Sophie DELHAY ist Dozentin und Architektin. Sie ist assoziierte Professorin an der EPFL Lausanne (Schweiz) – wo sie den Schwerpunkt „Wohnen“ koordiniert und das Forschungslabor Domestic-city Lab leitet. Sie arbeitet in Paris, erhielt 2019 den Architekturpreis „Equerre d’argent“ in der Kategorie „Wohnen“ und wurde 2022 mit dem Schelling-Preis für Architekturtheorie ausgezeichnet.

Sie widmet sich vornehmlich der Frage des Wohnens und stützt ihren Ansatz darauf, dass dieses Thema die meisten Menschen betrifft, dass die Architektur eine Stadt am stärksten prägt und somit einer der wichtigsten Hebel ist, um die Welt zu verändern. Auf diese Weise versucht sie auch, der Wohnarchitektur – die oft als niedere Kunst angesehen wird – wieder zu neuem Ansehen zu verhelfen. Sie erprobt, wie sich die Architektur – im kleinsten Maßstab und durch ihre Bewohner – positiv auf die Entwicklung der Gesellschaft und das Klima auswirken kann.

Lauriane Gricourt

Lauriane Gricourt ist seit Januar 2024 Direktorin von Les Abattoirs, Musée – Frac Occitanie Toulouse. Sie studierte Kunstgeschichte und Museumskunde an der École du Louvre (Paris). Ihre Forschungsarbeit konzentriert sich auf körperliche und performative Kunstformen.

Sie ist zudem Gründungsmitglied des Collectif Enoki, mit dem sie an Projekten zu Verbindungen zwischen Kunst und Ernährung an Orten wie dem MAC VAL (Vitry-sur-Seine), der Zone sensible (Saint-Denis) und dem UNESCO-Lehrstuhl für Welternährung an der Universität Montpellier arbeitet. Sie war Projektleiterin am Musée Maillol (Paris), Verantwortliche für die Sammlungen der Carmignac-Stiftung (Paris-Porquerolles), leitende Kuratorin der Cartier-Stiftung für zeitgenössische Kunst (Paris) und von 2022 bis 2024 Kuratorin für Ausstellungen im Museum Les Abattoirs. Dort war sie u. a. Ko-Organisatorin der Ausstellungen der Künstlerinnen Shona Illingworth, Liliana Porter, Tabita Rezaire und der Gruppenausstellung „Artistes et paysans. Battre la campagne“, die noch bis zum 25. August 2024 gezeigt wird.

Jan Liesegang

Jan Liesegang ist eines der Gründungsmitglieder des Architektenkollektivs raumlaborberlin. raumlaborberlin arbeitet in verschiedenen interdisziplinären Teams zu den Themen Stadtplanung, Architektur, experimentelles Bauen, Kunst und Forschung. Ihre Arbeit konzentriert sich stark auf die Erneuerung öffentlicher Räume im Rahmen von prozessbasierten, partizipativen Projekten. Diese Projekte reichen von zahlreichen mobilen Pavillons bis hin zu groß angelegten Stadterneuerungsprojekten.

In seiner Arbeit und Lehre interessiert sich Jan besonders dafür, die Grenzen der narrativen Dimensionen in der Architektur auszuloten und die Identität städtischer Räume zu stärken. Zu Jan Liesegangs neuesten Projekten gehören der kürzlich eröffnete öffentliche Park, die Sauna und das Flussbad im ehemaligen Freihafen von Göteborg; eine Sommerschule und ein öffentliches architektonisches Erneuerungsprojekt in einer verlassenen Ziegelfabrik im Zentrum von Prishtina, Kosovo, im Kontext der Biennale Manifesta 2022 und die laufende Projektentwicklung für ein inklusives Künstlerhaus und eine Akademie in Zusammenarbeit mit X-SÜD, einem Künstlerkollektiv mit gemischter Behinderung, in einem ehemaligen Stahlwerk in Köln.

Seit 2017 ist er Professor für Architektur an der Architekturschule in Bergen. Jan Liesegang hat eine Reihe von Büchern über Praktiken der Zusammenarbeit und Arbeitsmethoden in verschiedenen Projekten mitveröffentlicht: “house of time / living in the now”, Triënnale Brugge, 2019; “Cantire Barca”, Reflexionen über das selbstgebaute Gemeinschaftszentrum in einem Vorort von Turin, 2016 “building the city together” über experimentelle Architektur und neue selbstorganisierte öffentliche Räume 2015.

MITKUNSTZENTRALE – Satellit

MIKTKUNSTZENTRALE ist ein Kollektiv aus Berlin, das seit 2021 in der Gast-Stätte SATELLIT gemeinsam mit der Nachbarschaft, mit Künstler*innen und Kreativen selbstorganisiert und mit künstlerischen Mitteln den sozialen und klimatischen Herausforderungen unserer Zeit begegnet. An der Fertigung von Gemeingütern arbeitet die MITKUNSTZENTRALE seit 2019 im Haus der Materialisierung, einem Zentrum für ressourcenschonendes Materialrecycling, das Teil des Modellprojektes Haus der Statistik am Alexanderplatz in Berlin ist. Hier entstehen skulpturale Designstrategien für das Bauen mit Gebrauchtem. Die MITKUNSTZENTRALE wird im Sommer 2024 im ZAK- Zentrum für Aktuelle Kunst/Zitadelle Spandau, Berlin eine EInzelausstellung gestalten.

An der Jury nehmen Martina della Valle (Fotografin, Künstlerin), Erik Göngrich (Künstler), Susanne Schröder (Kulturwissenschaftlerin) und Nora Wilhelm (Produktdesignerin) teil.

RANDOM KINGDOM – QUEERING NATURE: THE QUEST

Im August 2024 veranstaltet der Kunstverein Random_Kingdom in Berlin und Paris eine Kunstresidenz zum Thema Queer Ecology. Das Projekt bringt Digitalkünstler:in, Entwickler:in und Performer:in des House of Deathless Flowers der Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Die Denkfabrik erforscht die Intersektionalität der Queer-Ökologie, indem sie Fragen der sozialen und ökologischen Gerechtigkeit durch die Kunst integriert. Die Residenzwoche umfassten kollektive Rituale, Workshops, Diskussionsrunden und eine Rückgabe in Form einer Performance. Die während der Woche entstandene Quest wird virtuell auf der interaktiven Karte des Random_Kingdom im Jahr 2025 verfügbar sein und die Kunstszenen in Frankreich und Deutschland miteinander verbinden.

Naomi Cassim @random.kingdom.rk

Künstlerin und Gründerin Random_Kingdom

MUSEUM GRENZENLOS – MUSEES HORS-FRONTIERES

Anlässlich der 20-jährigen Partnerschaft zwischen der französischen Region Hauts-de-France und dem Land Nordrhein-Westfalen schließen sich die Kunstmuseen Krefeld und das FRAC Grand Large – Hauts-de-France für eine innovative Ausstellung mit dem Titel “Museum grenzenlos | Musées hors frontières” zusammen.

Das Projekt konzentriert sich auf die Disziplinen Kunst und Design, die die Schwerpunkte der jeweiligen Sammlungen der beiden Museen darstellen. In zwei Ausstellungen werden ihre fruchtbaren Dialoge und ihre Herausforderungen für die Gesellschaft beleuchtet. Es geht darum, die Museen als Bürgerplattformen zu denken, um in die Zukunft zu blicken und die langfristige Zusammenarbeit zwischen den Teams der beiden Museen fortzusetzen.

Von April bis September 2024 werden Schlüsselwerke aus der Sammlung des FRAC im Haus Lange Haus Esters sowie im Stadtraum von Krefeld ausgestellt. Im Jahr 2025 wird das FRAC wichtige Werke der Kunstmuseen Krefeld in Dünkirchen präsentieren. Das Kooperationsprojekt soll die kooperativen kulturellen Beziehungen zwischen Krefeld und Dünkirchen sowie zwischen den Regionen fördern. Ein weiteres wichtiges Ziel ist die Aufwertung von Kunstinstitutionen als Plattformen für den Austausch und die Beteiligung verschiedener Stimmen aus der Gesellschaft.

SLURS – SLAVS&TATARS

Wir leben in einer Zeit, in der Sprache in hohem Maße politisiert und instrumentalisiert wird: als Mittel der Aggression aber auch der Solidarität. Während letzterem viel Aufmerksamkeit gewidmet wurde, ist es ebenso wichtig, die Dynamik der sprachlichen Gewalt sowie ihre rhetorischen und philologischen Ursprünge sowie ihre affektiven Auswirkungen zu verstehen.

Das Projekt zielt darauf ab, die Geschichte der sprachlichen Gewalt zu untersuchen, wobei ein besonderer Schwerpunkt auf spezifischen geografischen Gegebenheiten und Gemeinschaftskämpfen liegt. Durch die Analyse von Schimpfwörtern, insbesondere von Ethnophaulismen (oder abfälligen Bemerkungen über ein Ethnonym), wollen wir die schmutzige Seite der Sprache freilegen um einen besseren Zugang zu den Strukturen der Gewalt zu erhalten. Es geht hierbei auch um die Erarbeitung notwendiger Werkzeuge für einen wirkmächtigen sprachlichen und performativen Widerstand gegen Angriffe auf race, Geschlechter oder Sexualität in lokalen Kontexten inmitten von globalisierten Sprachen.

Das Projekt Slurs a program about verbal violence in the form of a language protest wird sich mit bestimmten Dialekten und Beleidigungen befassen, die für lokale Sprachen spezifisch sind. Während Slavs and Tatars Osteuropa, den Kaukasus und Zentralasien aus der Perspektive einer Minderheit in Berlin betrachten, erweitert das Projekt diesen geographischen Rahmen, indem es sich auch mit dem Wissen und der Forschung der Diaspora im französischen Kontext beschäftigt. Zu diesen Sprachen gehören das jiddisch-ukrainische in Odessa oder ein russisch-georgischer Dialekt, der nur im Zusammenhang mit einem Markt, der Autoteile in Tiflis verkauft, verwendet wird, aber auch arabische Dialekte, Westarmenisch oder Kreolisch in Paris.

In der ersten Phase werden die in Frankreich und Deutschland ansässigen Teilnehmer:innen ihre Forschungsergebnisse durch Online-Treffen austauschen. In der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 2023 werden zwei Studientage in den Räumlichkeiten von Relais Culture Europe zwischen dem Gare du Nord und dem Gare de l’Est in Paris veranstaltet. Schließlich werden im November und Dezember 2023 Performances in der Pickle Bar in Berlin organisiert.

Teilnehmer:innen:

Pickle Bar, Beyond the post-soviet collective, Relais Culture Europe

Veranstalter:innen:

Slavs and Tatars (Deutschland), Relais Culture Europe (Frankreich)

NILS ALIX TABELING – BUT WHO IS ULRIKE MANDRAKE

“Fleur de peau, terre à vif / But who is Ulrike Mandrake” ist eine zweiteilige Ausstellung an zwei Orten, die die Arbeit von Nils Alix-Tabeling, einem jungen französischen Künstler, der in Montargis lebt und arbeitet, vorstellt. Nils Alix-Tabeling setzt sich durch verschiedene Medien mit dem Erbe des Terrorismus der 1970er Jahre auseinander: Malerei, Performance, Klang und Objekte.

Der erste Teil “Fleur de peau, terre à vif”, der im Parvis in Tarbes, in Frankreich gezeigt wird, befasst sich mit den Wurzeln des Ökoterrorismus, unter Berufung auf radikale Denker:innen des 20. Jahrhunderts und durch die Untermalung mit dem “musikalischen Terrorismus” der deutschen Krautrock-Band Amon Düul.

Der zweite Teil “Ulrike Mandrake” setzt diese Überlegungen im Dortmunder Kunstverein fort. Nils Alix-Tabeling eignet sich hierbei die Erzählungen und Zeugenaussagen über den Umgang des deutschen Staates mit den Leichen der Mitglieder der Roten Armee Fraktion an. Er verweist auf die Figur der Journalistin und R.A.F.-Führerin Ulrike Meinhoff, deren Gehirn nach ihrem Tod aufgrund der Diagnose einer “emotionalen Störung” seziert wurde, um ihre Handlungen und ihr “vernachlässigendes” Verhalten gegenüber ihren Kindern zu rechtfertigen. Durch Skulpturen aus natürlichen und industriellen Materialien und gespenstisch anmutende Performances enthüllt Tabeling die Gewalt der Wissenschaft und des Staates gegenüber Körpern und insbesondere gegenüber weiblichen Körpern.

Die Ausstellung “Fleur de peau, terre à vif” wird vom 15.2. bis 07.07.2023 im Le Parvis in Tarbes und der zweite Teil “But who is Ulrike Mandrake” vom 25.06. bis 10.09.2023 im Dortmunder Kunstverein gezeigt.

Teilnehmer:innen:

Nils Alix-Tabeling (Künstler, Frankreich)

Veranstalter:innen:

Le Parvis, Tarbes (Frankreich), Dortmunder Kunstverein, Dortmund (Deutschland)